During the 1960s, AT&T's Bell Labs developed a video-calling platform known as the Picturephone.

In doing so, the company almost invented the internet. But after a few seemingly insurmountable struggles, it decided to end what was then the best hope of a world wide web.

The story begins with video calling, which is a lot older than you may think. The first patent was filed in Germany in 1932 by Dr. Goerg Schubert. Not long after, the German post office ran the first video calling service — between video phone booths in Berlin and Leipzig, and later to Nuremberg, Hamburg, and Munich — from 1936 to 1940.

World War II halted video calling in Germany, as well as another proto-video calling system run by the French post office. But Bell Labs really got the video-phone ball rolling after the war.

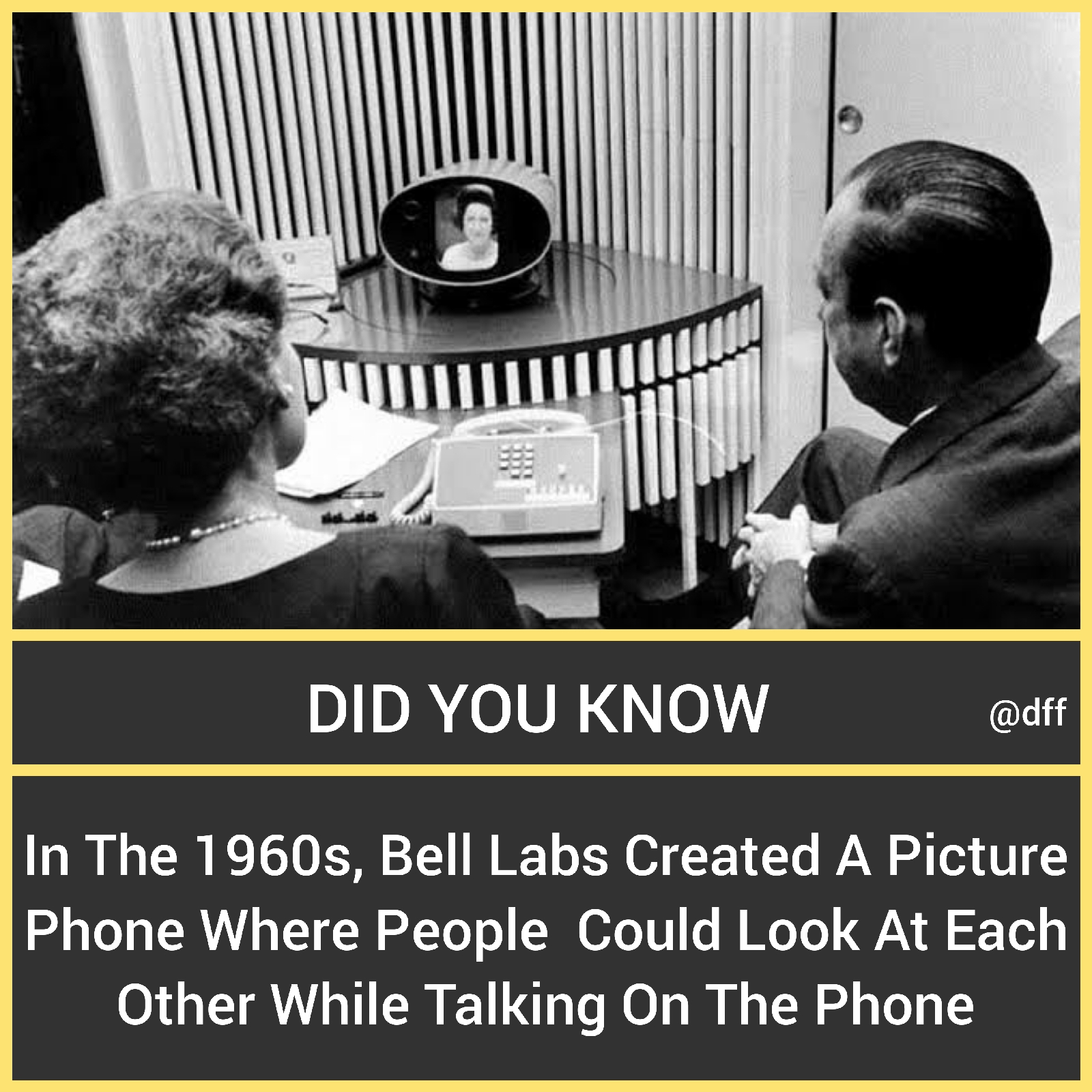

The American telephone company had been researching the technology and teasing prototypes for decades when it finally unveiled its Picturephone at the 1964 New York World's Fair. Their setup allowed fair goers to make transcontinental video calls to guests at Disneyland in California.

The device was actually pretty slick, with a five-by-five-inch screen in a cylindrical housing and a push-button phone (another new technology in 1964). The picture quality was crummy, and the small screen didn't help, but users were generally impressed with the device.

Bell Labs had big plans for video calling. They hoped it would raise interest in a broadband phone network — just like the contemporary ones used to connect landlines and internet.

The engineers also foresaw a future where our data would be sent over a high-power broadband connection (like Ethernet cables we use for modern connections) that could handle heavier loads than traditional "twisted pair" copper wire, which was used for telephone service at the time, according to a short documentary by YouTube's engineerguy, Bill Hammack.

Unfortunately, the Bell Picturephone was both too expensive for home use, and not powerful enough for businesses with the capital to pay for it.

Bell charged $160 per month for the service, and calling from one of the Picturephone booth set up in major American cities cost $20 a minute — about $1,200 and $150 in 2016's dollars. And you could barely see documents and conduct much business on the tiny display. (Try sharing a legal document on a very fuzzy screen the size of a sandwich.)

This exorbitant price kept interest in the Picturephone low, and kept Americans using existing copper telephone wires, which was still very capable of handling their voice calls.

In 1964, within the first six months of service, only 71 customers used the picture booths. And the technology ultimately failed to meet lofty goals set by Bell: 1 million Picturephones by 1980, and 12 million by 2000. So after sinking $500 million into the project, Bell pulled the plug on the Picturephone in 1978.

The Picturephone was a huge failure and arguably missed an opportunity to create the first widely used international network of computers — also known as "the internet."

Low demand, mixed with an inability to scale the groundbreaking (though expensive) new product kept the Picturephone out of homes, and kept an embryonic internet from growing past a telecom engineer's vision of the future. The general public world would have to wait until the 1990s before logging on.

Although it's amazing to think of what our world would be like if we had the internet in the '60s, remember: Hindsight is 20/20. You can hardly blame Bell Labs for cutting the cord on a project that lost them half a billion dollars.

Comments

Post a Comment