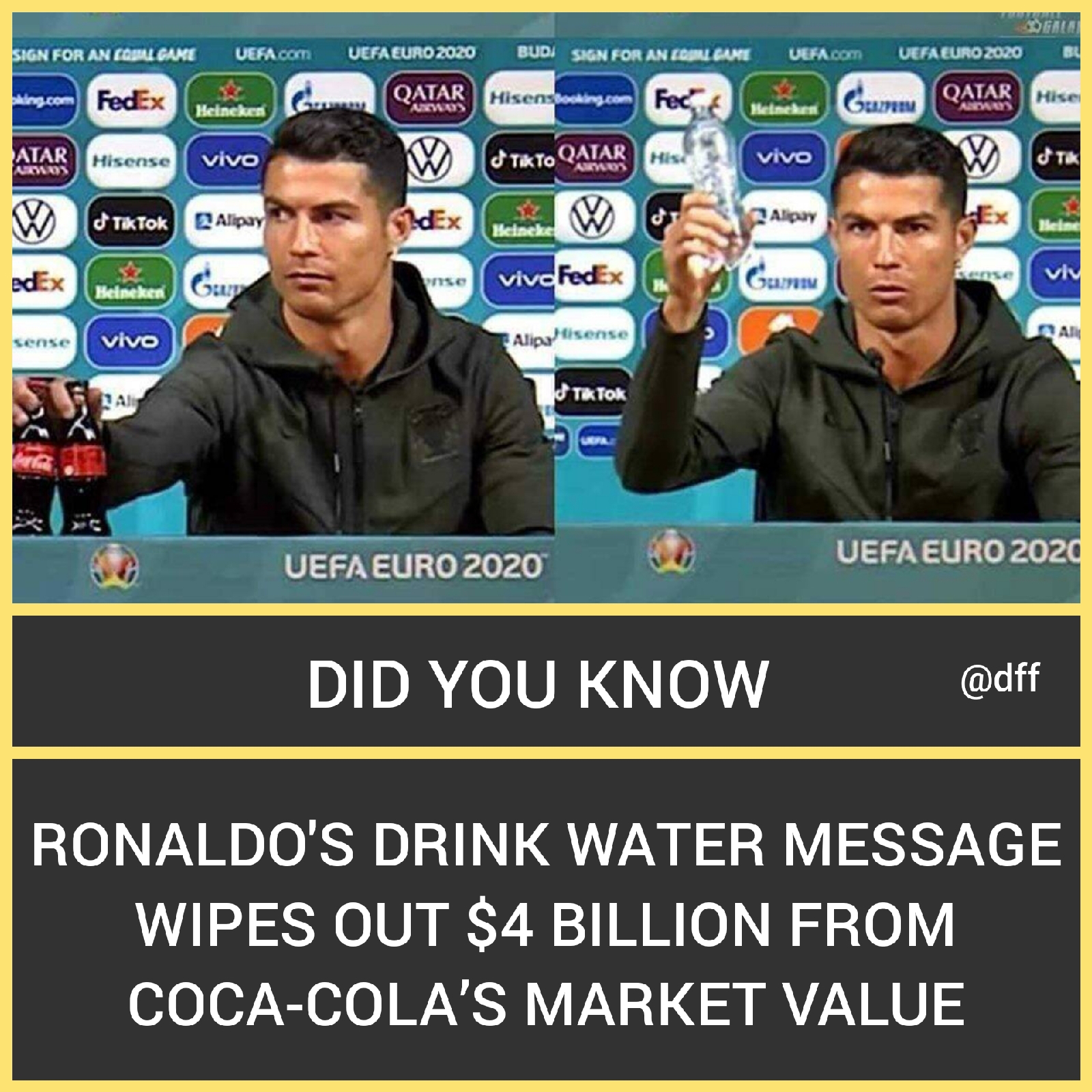

Cristiano Ronaldo’s decision to remove two Coca-Cola bottles from view at a press conference, and dent the value of the fizzy drink maker’s sponsorship of the European Championship, has highlighted the risks brands face associating with sports stars made powerful by the social media era.

The Portugal captain, a renowned health fanatic who eschews carbonated drinks and alcohol, underlined his point by holding a bottle of water while saying “agua”, Portuguese and Spanish for water. The water brand in question happened to be owned by Coca-Cola too, but the damage – by a major sports star with 550 million social media followers – was done.

“It’s obviously a big moment for any brand when the world’s most followed footballer on social media does something like that,” says Tim Crow, a sports marketing consultant who advised Coca-Cola on football sponsorship for two decades. “Coke pays tens of millions to be a Uefa sponsor and as part of that there are contractual obligations for federations and teams, including taking part in press conferences with logos and products. But there are always risks.”

Major brands have never been able to control the actions of their star signings. Nike decided, stoically, to stand by Tiger Woods as the golfing prodigy lost sponsors including Gillette and Gatorade after a 2009 sex scandal. However, Ronaldo’s public snub signifies a different kind of threat to the once cosy commercial balance of power between stars and brands, one born of the social media era.

“Ronaldo is right at the top of social media earners,” says PR expert Mark Borkowski. “It is about the rise of the personal brand, the personal channel, it gives so much bloody power. That’s what has allowed Ronaldo to make a point [about a healthy lifestyle].”

Now 36, the world’s most famous footballer has built an empire that has seen him make more than $1bn (£720m) in football salaries, bonuses and commercial activities such as sponsorships. What is crucial is the global platform social media has given him – half a billion followers on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook – which has freed him from following the commercial rules of clubs, tournaments and their sponsors. He is the highest earner on Instagram, commanding $1m per paid post, and with more than $40m in income from the social media platform annually he makes more than his salary at Juventus.

“People are saying this is about athlete activism and there is some truth to that,” says Crow. “Athletes are taking a more activist view, we are seeing that, most recently in press conferences. And we will see it again.”

On Tuesday, the France midfielder Paul Pogba, a practising Muslim, removed a bottle of Euro 2020 sponsor Heineken’s non-alcoholic 0.0 brand from the press conference table when he sat down to speak to the media after his team’s 1-0 win over Germany. Three years ago, he was one of a group of Manchester United stars who boycotted a contractual event for sponsors to protest at the club’s poor travel arrangements that had affected Champions League games.

Crow says the most important example of athlete activism came last month when Naomi Osaka, the No 2-ranked female tennis player, pulled out of the French Open after being fined $15,000 and threatened with expulsion by organisers for saying she would skip contractual media obligations because of the effect on her mental health.

Osaka, who has more than 4 million social media followers, used Twitter to explain her “huge waves of anxiety” and the “outdated rules” governing players and media conferences, and announce she was pulling out of Roland Garros.

“Activism is now on every sponsor’s radar,” says Crow, who believes Ronaldo’s move could mark the beginning of the end of product placement-laden press conferences.

“My view is that for a long time now having sponsors’ products on the table in front of athletes in press conferences looks outdated and inauthentic and it’s time to retire it,” he says. “This incident highlights that fact. Many of my sponsor clients have mentioned this in the past, particularly those targeting younger consumers. It’s not as if sponsors don’t have enough branding throughout tournaments and events anyway.”

Comments

Post a Comment